|

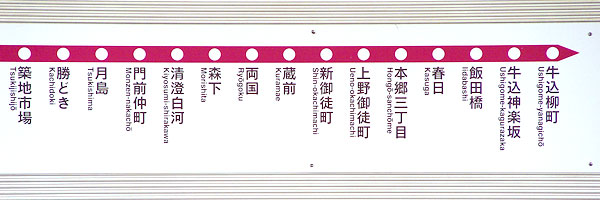

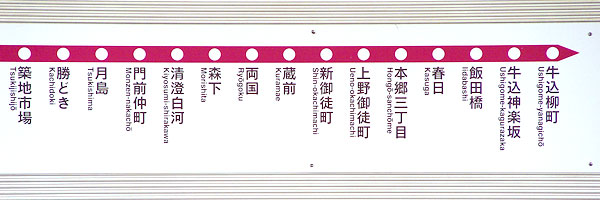

| Oedo Line |

Dominic Armato |

I was thrilled to return to China. I love the food. I love the chaos. I love the gritty edge of Hong Kong and the cities in Guangdong. But I'd be lying if I didn't admit that the part of the trip that ate up the bulk of my planning and anticipation was the three days we'd spend in Japan before returning home... two full days with half days on either end. If I love China (and I do), I LOVE Japan. From the love affair with electronics, to the clean and minimal design sensibilities, to the obsession with perfecting food at every level, this is a culture that pushes all of my buttons, and no matter how much time I spend there it's never enough.

So we opted to maximize it. Rather than a Sunday morning departure from Hong Kong, we took a Saturday night red eye, arriving early in the morning, ready to hit the ground running and earn ourselves another half day. Thankfully, work in Japan involves packaging research, and cruising department stores and shopping areas is a whole lot more conducive to squeezing in good eats than twelve hour days visiting factories. What's more, Sunday morning Tokyo traffic is, mercifully, a whole lot more conducive to one's continued sanity than the weekday version.

|

|

|

|

Sandwiches |

Dominic Armato |

|

After a bus to the station, taxi to the hotel, quick stop check in and drop off bags, it was time for a quick cup of coffee before hitting the stores. Coffee accomplished, but I also can't escape a trip to Japan without indulging an old obsession. It's one that I can't explain or justify, but these little sandwiches are everywhere in Japan, and I love them. Egg salad, potato salad, tuna salad, some tomato and cucumber, maybe a bit of ham and cheese, all layered between the softest, squishiest crustless sandwich bread you've ever encountered. What's the appeal? No idea. On my early trips to Japan, these fellows constituted breakfast and snacks while riding the shinkansen on numerous occasions. Nostalgia, perhaps? In any case, these usually cellophane-clad fellows are an inexplicably indispensable part of any trip to Japan for me. Coffee and sandwiches consumed, it was off to Ginza.

Ginza is Tokyo's upscale shopping nexus, where small boutiques sell items for insane prices, premium brands occupy entire lowrise buildings, and huge department stores cater to the well-heeled. It's the latter that's our target, both for work and pleasure, where the basements are packed with amazing eats. Take your average supermarket, triple the size, then fill it with stands selling premium foodstuffs of every kind. Culturally speaking, the Japanese have a special love of quality. Culinary delights from all over the world, the best of the best, are all packed into one place. Or, in the case of the Ginza strip, three or four of them in a five block stretch.

Jamon Iberico de Bellota, anyone? A mere $4200 per leg. And you have your choice of eight. Strawberries, stunningly perfect, unblemished, each better than the most perfect strawberry you've ever tasted, packaged in a wooden box and sold for $50/dozen. Japan's famed beef, currently illegal in the United States (a retaliatory embargo after Japan cut of U.S. beef due to BSE concerns), marbled such that it seems more fat than meat, this particular specimen a good bit off the pace at $130/lb (I'd later find some at $500/lb). Of course, these are the shocking outliers. But what's clear is that there's an appreciation for food quality in Japan that you just don't see in the United States. Most of what you'll find in basements of the department stores is affordable, if somewhat expensive. But even run of the mill produce is stunning in appearance and freshness, meats trimmed with the utmost care, confections stunningly presented, as with the cake above, each slice carefully packaged, each flavor artfully topped with a different assortment of nuts, berries and sugared herbs. And these are but a few examples out of thousands and thousands. I could fill two dozen posts with similar finds. At first it's awe-inspiring to see so many of the most incredible foods you've ever seen all collected in one space. Then it's frustrating, as you start to ask yourself why we can't have just a tenth of this back home. Then it's depressing, when you accept that on the whole, we just don't have the cultural appreciation for quality necessary to support places like these. When it comes to food in the United States, on the project triangle of cheap, fast and good, it's no mystery which one is usually sacrificed. I try not to dwell on it lest every blog post devolve into an angry rant.

|

|

|

| Tomato Salad |

Dominic Armato |

|

And what better way than taking a lunch break to avail ourselves of some of these amazing ingredients? Zakuro is another old favorite, in the heart of the Ginza strip, specializing in shabu shabu. It's tucked away in the basement of an office building, old-school in appearance with paper screens and a kimono-clad waitstaff, and an air of propriety that's reflected in the food. We started off with a tomato salad, topped with a scant amount of finely chopped onion, heavily dressed with a vinaigrette and arriving in a small bowl encased in ice. The color, though vibrant, was off-putting at first, something I'd associate more with underripe tomatoes -- which I'd never experienced at this restaurant. And this would be no exception. It was ice cold, sweet and fabulous. A clean, fresh start.

|

|

|

|

Goma Su |

Dominic Armato |

|

Shabu shabu is a particular breed of nabemono -- Japanese pot food -- that's on the blissfully simple end of the spectrum. You boil some water along with a slice of kombu for a touch of umami depth, and do a little cooking at the table. Though it's been expanded to include a substantial variety of ingredients in some parts, its simplest, most traditional form involves little more than very thinly sliced raw beef accompanied by a variety of fresh greens, mushrooms, tofu and perhaps noodles. In go the vegetables, you take a slice of beef and swish it around for a few moments, and on their way out both are dipped in either a ponzu or goma-su (sesame sauce), and maybe a small bowl of steamed rice joins the party. That's it. There's not a whole lot to it. Which means the only thing separating the good from the bad from the stellar is the quality of the dipping ingredients, and the preparation of the sauces. And here's where they start to tease you.

|

|

|

|

| Vegetables |

Beef |

Dominic Armato |

First come the sauces, and it's all I can do to keep from drinking the goma-su right there. This sweet and nutty dip made with ground sesame, soy, sugar and vinegar (and perhaps punched up with an aromatic or two) is good even when it's bad, as in many cheap places when you're getting what's most likely a bottled product. But when it's painstakingly made from deeply roasted and freshly ground sesame as it no doubt is at Zakuro -- heightened with a hint of garlic, a few floating globules of chile oil, and freshly minced chives -- we're entering "I could drink a quart of that condiment" territory. The ponzu's no slouch either, and sneaking a sip before the rest of the setup arrived, I was reminded of what fresh yuzu tastes like, as opposed to the bottled juice used at all but the most ultrapremium restaurants in the States. Then they taunt you a little more, laying out a platter of pristine vegetables, perfectly sliced and arranged and ready for a magazine photo shoot. And then, there's the beef. I think they used to offer lower grades at Zakuro, but now the bidding starts at A5 Wagyu and goes up from there, and it shows. I almost -- *almost* -- cringe at the thought of tossing this beautiful beef into boiling water, but this isn't the stuff of Chef Hicks' nightmares. They have far too much reverence for ingredients like this to screw them up.

|

|

|

| The Pot |

Dominic Armato |

|

Finally... *finally*... the pot arrives, and rather than the simple stainless job on an induction burner that typify the quick lunch spots, here it's an elaborate contraption of hammered copper, a raised donut-shaped bowl surrounding a chimney nearly three feet tall, a charcoal fire within the base providing the heat. It's needlessly ornate. I can't imagine anything a charcoal heat source brings to the table that an induction burner doesn't, other than various levels of complication in maintaining your heat. But as with so many Japanese traditions, it's as much about the process as it is about the results, and even if they're short on practicality they're usually long on beauty, which is certainly the case here. Finally, we dive in, and while the first round of vegetables cooks, I gently peel off that first paper-thin slice of beef, give it a few quick swishes through the water so that there's a little pink where my chopsticks are holding it, pause for a moment to dip it in the goma-su, and then enjoy a melting mouthful of what's as much beef fat as it is meat, silky smooth, tender and juicy, and completely unlike any slice of cow attainable back home. I savor it -- I'd better, since the stuff probably costs about $15 per slice -- before moving on to some fresh greens, scallions and mushrooms, giving them a splash of citrusy ponzu as they escape the pot. Wait... what's missing... rice! "Gohan, onegaishimasu," I say, exhausting close to 5% of my Japanese vocabulary in one loquacious burst (Kiguchi Sensei's class back in high school was big on kana, not so much on conversation), and moments later I'm reintroduced to the beauty of a bowl of perfectly steamed rice, remembering that it isn't just an accompanying starch, but can be a fabulous dish all its own. So we dip and slurp and moan and don't talk much until each has but one slice of beef left -- naturally, you have to save one slice of that beef for the last taste -- and that last taste is as bitter as it is sweet, because I could eat a week's salary worth of this beef in one sitting and it still wouldn't be enough.

|

|

|

|

Broth |

Dominic Armato |

|

Of course, the meal isn't quite yet over. Large mugs and a small copper ladle appear, and after filling the mugs with some of the cooking water left in the pot, we add a dash of salt from a tiny carved wooden box using a tiny carved wooden spoon, and a large spoonful of minced chives, and spend a few minutes sipping the scalding hot broth while longing for another plate of the beef that enriched it. This is why we keep coming back, despite the questionable price performance. Lunch was over $100 each, the most expensive meal we'd have on this trip. And though it's easy to do so, you don't need to spend big money to eat like a king in Tokyo. But the ritual, the tradition, the simplicity and the pure reverence for perfect premium ingredients is such an ideal way to kick off a trip to Japan that we get sucked in every time. It'd be a damn fine meal without all of the cultural subtext. But with it, it's irresistible. It's as much habit as anything at this point, but I have a hard time imagining a trip to Tokyo without a stop at Zakuro.

|

|

|

| The Door |

Dominic Armato |

Now more than 32 separated from our last crack at a pillow, we did a little more wandering for work and then headed back to the hotel for a much-needed break before dinner. One breed of restaurant that I'd barely experienced on previous trips, much as it pains me to admit it, are the izakayas; the cozy, casual neighborhood joints that kind of fly under the radar, where unpretentious food meets generous amounts of beer and shochu (and, to a lesser extent, sake). So I resolved to hit a couple on this trip, and one name that popped up a few times during my searching was Nakamenoteppen. Navigating Tokyo is a challenge. The addressing system is based on blocks as opposed to streets, so a detailed map is an absolute necessity, and even finding the right block might only be half the battle. Particularly in the higher-density neighborhoods (and I stress highER), Tokyo is the only city I've visited that requires you to navigate in three dimensions. If you're trying to get to a store or restaurant in most cities, knowing the North, South, East and West of things will put you close enough that you can spot it. But in Tokyo, being at the exact coordinates means that you could be facing a line of narrow buildings, not numbered in sequence, each with stores and restaurants going up five or six stories, and perhaps two or three floors down. On previous trips, there have been occasions where I've spent half an hour looking for a place, never walking more than 50 yards away from it. And I generally consider myself a strong navigator, even in three dimensions. But one of the lessons of this trip was that smartphones and Google maps were made for navigating Tokyo, and after easily locating the front door to Nakamenoteppen (thanks in no small part to some earlier Streetview scouting), we were faced with our second navigational challenge... the door itself. I lament the fact that there's nothing for scale in this photo, but the top of this door frame from which those pillow-looking things are hanging is about chest high. The wooden placard is somewhere around your belly, and the top of the actual door -- below the roll of fabric -- is about belt high. Whether the owners are students of some ancient Japanese tradition or merely possessed of an odd sense of humor, I have no idea. But I confess that practically crawling through the front door does give the sense that one is journeying rather than merely stepping across the threshold, and only heightens the illusion that you've entered a little self-contained world as you emerge on the other side.

|

|

|

| The View |

Dominic Armato |

You're first hit by the warmth, as a huge charcoal grill is situated directly in front of the door, right in the middle of what can rightly be described as a cave of a restaurant. As your head crosses the threshold, the shouted greetings hit your ears, welcoming you in traditional fashion. As you start to stand up, sweet, intoxicating smoke hits your nose, and once you've regained your balance you finally see the source, an abundance of fresh vegetables and seafood proudly displayed in front of the massive grill, and the bald, friendly, solidly built fellow manning it. Half of the room is jammed with small tables, the other half comprised of the open kitchen and long bar curving around it, with low seating that may be a stool and may be a milk crate with a piece of carpet lashed to the top of it, depending on where you're parked. Low ceilings, acoustic tiles, the heat emanating from the grill and the complete lack of windows somehow manage to lend a vibe that's cozy more than claustrophobic (Here's a shot that gives a better sense of the space), like a hobbit hole of the Eastern tradition where you could nestle in and warm yourself with good food and spirits and company all night. So that's what we did.

|

|

|

|

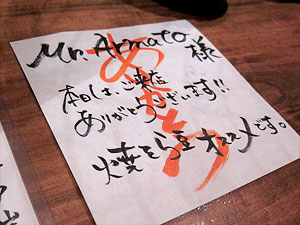

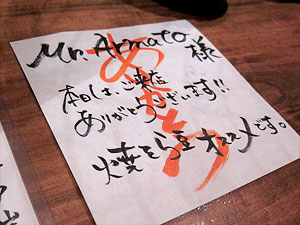

Welcome Note |

Dominic Armato |

|

Our hotel had called ahead to hold us a couple of seats, and waiting for us at the counter was a charming little missive, addressed to me, that I wish I could read. I got my name as well as the thank you in red in the background, and that's about it. Conversing with our hosts proved to be no less challenging, though they were warm and boisterous and couldn't have been more welcoming, even if the awkward moments of failed communication were abundant (I blame only myself). The fact that so much of their product was laid out on the counter was a godsend, and before long we were pointing and nodding our way to a lengthy order of items -- fish, flora and a few helpings of shochu -- and before long a beautiful parade of dishes, sent at a lazy, booze-friendly pace, started to arrive.

|

|

|

| Nasubi |

Dominic Armato |

|

Displayed directly in front of us were nasubi (Japanese eggplant), deep purple, narrow and two feet long, so that was a gimme. After starting it on the grill, the chef at one point lifted it up and buried the nasubi directly in the coals, leaving it there for a while to char and soften. When he removed it, after giving it a chance to cool, he rinsed it and skinned it like an eel, plating the inner flesh -- with just a little outer char left behind -- and serving it to us along with a bowl of shaved bonito and a small bottle of soy sauce. Humble doesn't begin to describe it. But more does delicious eggplant need than some fire and a little bonito and soy? It was silky smooth, the pulp having been cooked down to an almost mushy soft texture, and the little bonito and soy accent was all it needed. This was a great, simple start that completely set the tone.

|

|

|

|

Hotate |

Dominic Armato |

|

I'm a total sucker for scallops, and hotate is within the scope of my Japanese food vocabulary, so these fellows were next, served atop a searing hot shell that acted as its vessel through the entire cooking process. I'm not sure if the flesh of the scallop ever actually touched the grill, but if it did, it was only very briefly. It spent most of its time protected from direct fire by the shell, cooking and bubbling away in its own natural juices while absorbing the smoke that swirled around it. This received, I believe, no more than a splash of soy, and it probably didn't even need that. This was fresh seafood and smoke, tender and sweet, a little color and char where it had rested against a bare portion of the shell for a while, the muscle served along with just about ever other edible part of the beast. At this point, we were starting to wonder if the entire meal would be this minimal, mostly because we were hoping it would be.

|

|

|

| Tsubodai |

Dominic Armato |

|

I have no idea what tsubodai is. Some kind of whitefish? The varieties of fish available in Japan outnumber those readily available at home by two orders of magnitude. The set of fish that I could only describe as "some type of [blank]" might cover dozens of uniquely named varieties, ages and cuts of fish to an educated Japanese palate. But in any case, the tsubodai -- whatever it is -- seemed to be a special for the evening, and special was the right word. This one bore the full brunt of the grill, the skin side turning charred, blackened and flaky while the flesh side took on a robust golden color. Yet the flesh remained flaky and moist inside, the perfect marriage of fish and fire, with nothing more than some shredded daikon and soy to accompany. I ask myself why we can't have such brilliant, simple fish dishes at home, and then I remember that it's because the fish has to be this fresh and amazing to begin with. We aren't blessed with Tsukiji a short drive away, so it requires an appreciation for the best and a willingness to pay for it, and it's frustrating that those who understand this are so few and far between. But I digress.

|

|

|

|

| Makomo Dake |

Tamanegi |

Dominic Armato |

We piled on the vegetables. A bulbous onion of some sort was also parked directly in front of us. "Kore wa nan desuka?" (There goes another eight percent.) I'm still unsure whether tamanegi is a specific type or a catchall term, but yeah, I suppose this particular variety did kind of resemble Chop Chop Master Onion. It was trimmed, wrapped in foil and buried in the coals for 10-15 minutes, emerging as a sweet, tender and lightly caramelized roasted onion that practically melted at the touch. Through a convoluted flurry of stammering and pointing (I was into my third shochu at this point, which probably wasn't helping matters), we ended up with a chef's recommendation of makomo dake, young bamboo that was charred and served with salt and yuzu. It was absolutely delectable, surprisingly tender and sweet.

|

|

|

|

Tsukune |

Dominic Armato |

|

Somewhere along the line, I spied a plate of tsukune heading out to another diner and practically fell over myself trying to catch our hosts' attention. This is Japanese comfort food right here, ground seasoned chicken slapped on the grill and basted with a thick, sweet soy sauce. Essentially, what we're talking about here is Japanese meatballs, and it's easy to see how a shochu-fueled appetite would find them irresistible. I certainly did. They had a great texture, were aggressively seasoned but coated with a lighter glaze (my preference when it comes to tsukune), and served alongside a deep, vibrant orange egg yolk, just in case they weren't already rich enough. The only bad thing about these was that there weren't enough of them. I was ready for a dozen. We received two. Tempting as it was to try for more, we moved on.

|

|

|

| Bacon and... Something Green |

Dominic Armato |

|

I'm still not sure what the center of this little package was, but the exterior was bacon, and that was enough of a selling point right there. From across the counter, I'd initially thought it was asparagus, but was told no, it was... something else. I didn't catch the name. They were long, thin green shoots, but upon closer inspection it was clear that the buds at the end were of a very different shape, and the stalks appeared to be hollow as well. The bacon was thick, much subtler than American bacon, not nearly so salty or smoky, but possessed of the requisite amount of cured pork fat that sizzled and melted on the grill, making for a crisp and juicy package once fully cooked. They do pigs about as well as they do cows in Japan, which is to say it was fabulous.

|

|

|

|

Hamachi Collar |

Dominic Armato |

|

We couldn't bear to leave without one more piece of fish, so we rounded out the evening with a simple grilled yellowtail collar, and all propriety went out the window as I gnawed and sucked every last little sweet and charred bit from the bone. It was a fabulous meal, and the tsukune aside, not a single plate contained more than three ingredients, most no more than two. It was purely a function of fresh fish, fresh vegetables, a bunch of charcoal and a little knowhow. But as I've said too many times already just in this first post, they appreciate good ingredients. The punchline of our visit to Nakamenoteppen came when we tried to exit. As my father started to stoop at the front door, the staff started yelling something and frantically waving him off. One of the servers showed us around the corner, quite literally not three feet from where we entered, where a second secret full-sized door opened into the same entrance vestibule. We hadn't had that much shochu, but apparently they took pity on us nonetheless.

After accompanying my father back to the hotel, I resolved, fortified by liquid courage and a determination to make the most of every free moment, to go in search of some ramen before calling it a night. I'd mapped out a couple dozen that sounded particularly promising, giving special emphasis to those open late at night, and decided that my first bowl for the trip would come from Gogyo, which I'd read serves a killer bowl of ramen with a contemporary spin -- burnt miso.

|

|

|

| The Kitchen |

Dominic Armato |

Though Gogyo has a few locations strewn throughout the city, the one I'd scouted is in Nishiazabu, in a very quiet (at this late hour, anyway) residential neighborhood off the main drag a short walk west of Roppongi station. It's a casual late night joint, though it isn't lacking for high design, hewn from black stone, the tables and counters made of thick slabs of wood with a deep, reddish lacquer, the walls covered with red tile and a gleaming hammered copper backsplash lining the entire rear wall of the open kitchen. It's a room that evokes fire and brimstone, and I smirked as I considered that the kitchen seemed more suited to a hunchbacked Oliver Reed with Uma Thurman on his arm than the fellow who actually manned it on this particular evening. As it turned out, however, this slight, smiley fellow was no less a master of fire. Though I missed the shot, upon ordering a bowl of the house special ramen, he'd start heating a large wok, and shortly thereafter a huge blast of six foot flames would jump out of it. When they died down he'd add the contents to the dish he was carefully constructing, and moments later a black bowl of soup would come out of the kitchen.

|

|

|

| Burnt Miso Ramen |

Dominic Armato |

|

By black I don't mean the bowl (though it was also black), but rather the soup itself. Gogyo slings a tonkotsu broth, but you wouldn't know to look at it, since it's mixed with some kind of miso that been charred to a deep black color in the wok before being mixed into the broth. Though the bowl was full of noodles, I could only see them barely peeking out where they came within a few millimeters of the surface, because the depths of the bowl were completely impenetrable to the eye. A slice of pork, piece of fish cake, barely set egg and a small sheet of nori... it looked normal enough on the surface, though the flavor was anything but. I slurped a bit of broth and was astounded. It had that tonkotsu depth and richness, but it was charred, leaving what looked like flecks of carbon on my spoon after every slurp, like they'd figured out how to blacken a liquid, lending it that smoky, bitter complexity that was beautifully balanced by the inherent sweetness of the pork and miso. Vulcan and Venus was an even better metaphor than I'd realized. Add to this a thin slick of hot oil on the surface, and I can say without the slightest reservation that this was the biggest, boldest, most intense bowl of ramen I've ever tasted. But its fabulousness didn't end there. The noodles, kinkless and cut like thick spaghetti, had a bite that went beyond formidable. They weren't just firm. They weren't just chewy. They fought back, and it was an incredible pleasure to fight them. The pork was silky and tender and laden with fat, the egg would have been liquid if it had been cooked just a degree less, and the entire concoction was completely unlike anything I've ever tasted before. I know I'm a sucker for big flavor, but this was huge flavor paired with fabulous depth and balance. I didn't know it at the time, but this would turn out to be my favorite dish of the entire trip to Japan.

I stumbled out, completely dazed. I'd burned the hell out of my tongue on that hot slick of oil, but completely didn't care. I'd walked fifteen miles that day, I hadn't slept in a bed in almost 48 hours and I could barely feel my extremities anyway. I needed a few hours to digest and recharge, but I had a belly full of fire and I was just getting started.

| Zakuro |

| Tokyo-to, Chuo-ku |

| Ginza 4-6-1 |

| 3535-4421 |

|

| Nakamenoteppen |

| Tokyo-to, Meguro-ku |

| Kamimeguro 3-9-5 |

| 5724-4439 |

|

|

Whoa, a Baron Munchausen reference! I thought I was the only one who ever saw that movie.

Posted by: Glen | February 13, 2012 at 10:55 AM

Wow - what a meal that was at Nakamenoteppen. I never would have done this on my own. This really was perfection on so many levels. A real joy to have experienced.

Posted by: KA | February 13, 2012 at 10:28 PM

What a fabulous report! All I can say is thanks.

Posted by: DF | February 15, 2012 at 08:32 AM